#56: A journey through time with loess deposits

Loess deposits are an excellent source of information and are therefore used to reconstruct environments and climates in former times. A master's thesis investigated different soil profiles in Poland.

Loess is a sediment deposited by the wind. It is used in the field of geochronology to reconstruct the changes of past environments and climates. But what is loess exactly? It belongs to the most fertile soils in the world, mainly due to its silt content of up to 90%. This ensures the supply of plant-available water, soil aeration, extensive penetration by plant roots and ease of cultivation. Due to its high amount of silt, loess is easily transported by wind and its deposits can thus be found on the lee site of hills. These loess deposits can be used to draw conclusions about the origin of the wind-blown dust, the time of the deposition or what impact they have on soil formation.

Loess deposits in southwestern Poland

In this master's thesis five different soil profiles in Lower Silesia (Poland) were studied. The goal was to investigate the heavy and clay minerals, but also to study the geochemical and physical soil parameters. When bedrock weathering occurs, certain minerals are released. The types of minerals and the geochemistry vary along with the bedrock. The same pattern is observed in loess deposits. When loess weathers, certain minerals are released and transported to deeper layers of the soil and contribute to the development of soils. From existing literature, we know that through the weathering of these minerals, soil types like Luvisol or Alisol can develop.

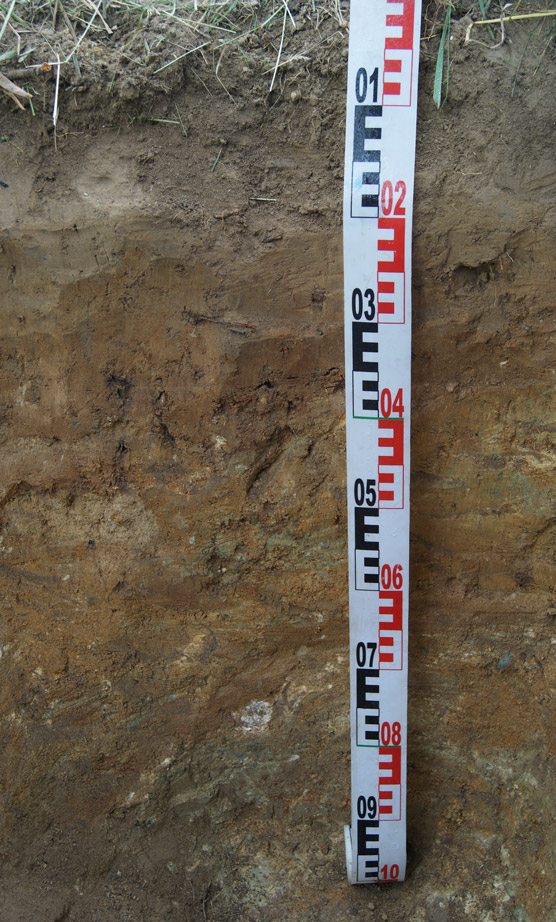

For this master's thesis five different bedrocks were chosen: Permian sandstone, basalt, granite, serpentinite, and glacio-fluvial material. To trace back the minerals to the loess or the bedrock, each profile was divided into three horizontal sections. The subdivision of the profile should help to understand which minerals originated from the bedrock and traveled upwards and which minerals were from the loess deposits and moved downwards.

Origin of the loess

Consequently, the first research question was which minerals have their origin in the loess deposits and which minerals originate from the underlying bedrock. The second research question dealt with the origin of the loess deposits. Do all five study sites have the same loess source or are there differences in geochemistry which could give a clue of their origin?

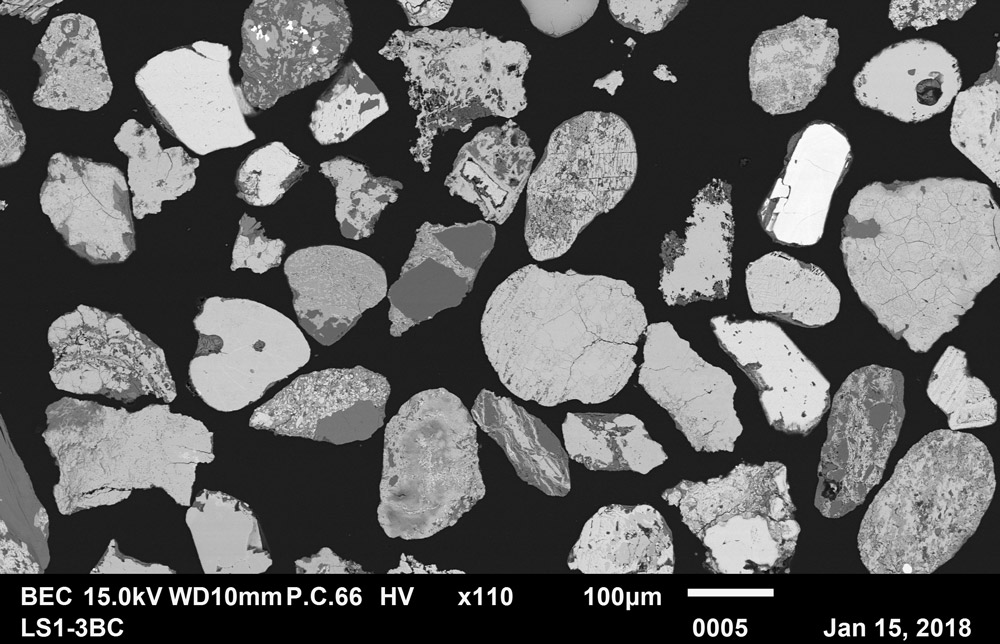

We discovered different mineral and geochemistry patterns between the five soil profiles. Additionally, observing the three sections in each profile we found different dominant minerals in each section. Hereafter, an example is shown with the soil profile having basalt as underlying bedrock. In the distribution of the heavy minerals we observed a high amount of the minerals ulvospinel, olivine and pyroxene near the bedrock while these three minerals showed a content decrease towards the surface. The mentioned minerals are characteristic for basalt and were interpreted as its weathering products.

On the contrary, we observed higher amounts of zircon or rutile in the upper layers which are characteristic for loess deposits. Regarding the clay minerals, transformations were observed due to weathering. In all loess deposits higher smectite contents were found which are a typical transformation product of the clay mineral mica. The clay minerals also provided insight into the downward clay translocation and thus helped to understand how the different soil types developed. Consequently, the different underlying substrate and the covering loess deposits have an impact on soil formation.

The calculation of element ratios (e.g. Ti/Zr and K/Rb) revealed that the provenance of the studied loess deposits was comparable with results from Germany. Most probably the loess originates from the vegetation poor periglacial areas during Last Glacial Maximum when the Scandinavian ice sheet covered northern Europe, but the southern lying Sudety mountains cannot be excluded as a possible loess source because silt production occurs also in high altitude regions through frost shattering.

For a conclusive answer regarding the origin of the loess more data is needed. The results of this thesis contribute to basic research because little is known how loess deposits and different bedrocks affect soil development.

Martina Vögtli