Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) are an urgent call for action to reduce all forms of inequality and

deprivation as well as to preserve the nature of our planet. These goals are to be achieved by 2030. The SGDs

were developed as part of the UN Agenda for Sustainable Development and adopted by all United Nation Member

States in 2015. The UN (2021) state the importance of cross-country collaboration. The SDGs cover various topics

such as poverty, health, education, inequality, economic growth, and climate change. The different strategies

must be coordinated and should empower the achievement of the various goals (UN, 2021).

An annual SDG Progress report is presented by the UN Secretary General collaborating within the UN System. The

report is based on the global indicator framework and data produced by national statistical systems and

information collected at a regional level (UN, 2021).

Research Questions

This project concentrates on migration and remittance as parts of the SDG. Migration and remittance

both belong to goal 10: Reduced Inequalities. However, the impact of those is larger than that and

they influence the achievement of other goals, as well. In relation to the United Nation goals in general,

the research questions of this project are the following:

1) What migration flows did exist in the last 3 decades?

2) The pattern of global financial flows in the past years: Which countries did receive remittances and in which countries more money has been paid?

3) What is the linkage between the two phenomena?

Migration

Migration is a cross-cutting issue and is relevant to all seventeen SDG goals (Migration Data Portal, no date). It is crucial to understand migration patterns

because of its relationship to the goals above. Moreover, there is the SDG of ensuring safe, orderly, and regular migration

(UN, 2021). In the future, climate change is likely to increase permanent migration flows substantially (KNOMAD, 2016).

According to the Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD) (2016), the international community

lacks a framework to cope with the migration from the affected areas. This Web Page provides an overview of migration and

its aftereffect: Remittances.

Remittances

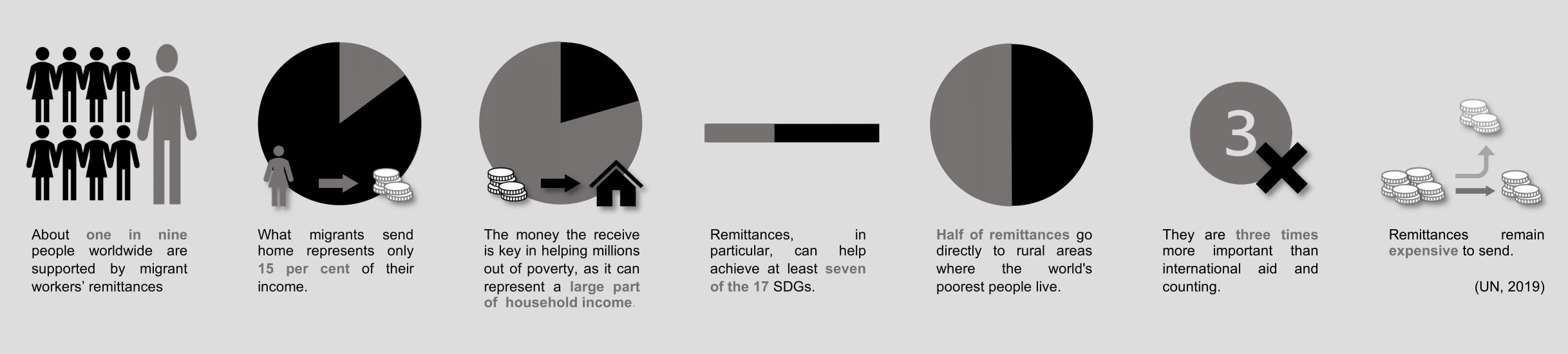

Remittances are household incomes from foreign countries that result from the temporary or permanent movement of people to

those countries (IMF, 2009). In the past years the interest in remittances increased and bridges between academic and political

spheres were created (Gubert, 2017). A specific United Nation goal is to decrease transaction costs (SDG 10.c) of migrant

remittances, as this is one of the most important and mature steps taken to increase incomes in developing countries

(IOM, 2017). Concrete examples in the Global Forum on Remittances, Investment and Development (GFRID, 2017) have shown how

migrant remittances and diaspora investments were reducing poverty and hunger and promoting access to health and education

(UN, no date). In addition, migration and remittances help cope with natural disasters and epidemics, as the diaspora can

assist in such situations (KNOMAD, 2016)

Dilip Ratha

Dilip Ratha is head of KNOMAD (Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development) and works at the World Bank as the

lead economist covering topics concerning Migration and Remittances, Social Protection and Jobs Global Practice. Over three

decades, he has done work on migration, remittance, and innovative financing.

He was born in a village in Odissa, India. Thanks to financial support, he first studied in a town close by, before he

fulfilled his dream to study in the United States. Crossing two oceans, Dilip Ratha only had a 20$ bill in his pocket.

While taking graduate classes, he worked in a research center. He sent part of his salary back to India to his father and

brother.

Dilip Ratha has a Ph.D. in economics from Indian Statistical Institute. He founded various organizations such as the African

Institute of Remittances. In his TED talk he talks about the potential of remittance and its global force in economics (World

Bank Blogs, no date; Ratha, 2014).

In order to approach the reduction of inequalities – especially the remittance costs, it is crucial to better understand the global pattern and dynamics of migration and financial flows between countries. According to the KNOMAD, which has the same objective, this knowledge can be used by policy makers in sending and receiving countries (Gubert, 2017).

Bilateral Migration Stock from 1990 to 2015

Estimated Migration

[number of people]

Net Migration (2010-2015)

[number of migrants per 1000 inhabitants]

Generation: Based on available data and modelled estimates

Definition: The UN defines immigrants or emigrants on the basis of country of birth. This results that a person that even acquired citizenship in the country of residence is considered as a migrant (UN DESA, 2020). For the purpose of analysing migration patterns and its relations with remittance data this definition appropriate because acquiring a citizenship does not mean that the contact with people in the country of birth is lost – hence remittance can still be sent back. However, if for a country data on the place of birth is not available, the country of citizenship is used as the basis of migrant status (UN DESA, 2020). This leads us to the problem the reliability and comparability of migration data.

Reliability: Migration data generation varies from country to country. The Map must be assessed critically for underestimated data. Therefore, this projects’ aim is to emphasize the need of reliable data for migration, as well as boosting the use of this data (Migration Data Portal, no date). It is necessary to help policy makers devise evidence-based policies to face migration aspects of the SDGs (Migration Data Portal, no date).

Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), Population Division (2020). International Migration Stock. Downloaded from Our World in Data. available here (accessed: 14.04.2022).

Generation:5-year estimates

Definition:Net Migration Rate = number of immigrants – number of emigrants (citizens & noncitizens) divided by population. The rate is expressed as average annual net number of migrants per 1000 inhabitants. A person living more than 1 year in a country other than country of birth is considered as a migrant (includes: students, refugees, foreign workers, etc.

Reliability:Migration data generation varies from country to country. The Map must be assessed critically for underestimated data. Therefore, this projects’ aim is to emphasize the need of reliable data for migration, as well as boosting the use of this data (Migration Data Portal, no date). It is necessary to help policy makers devise evidence-based policies to face migration aspects of the SDGs (Migration Data Portal, no date).

Source:United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), World Population Prospects: 2019 Revisions. Net Migration Rate. Downloaded from UN DESA. available here (accessed: 14.04.2022).

Worldwide Remittance Flows between 2017 and 2020

Amount of Remittances received and sent [Mio US$]

Generation: All numbers are in current (nominal) US $.

Definition: Remittances include all personal transfers and compensation of employees. The transfers consist of all transfers in cash or in kind and include current transfers between resident and nonresident individuals. Compensation of employees is defined as the income of border, seasonal, and other short-term workers who are employed in an economy where they are not resident. Furthermore, compensation of employees includes residents employed by nonresident entities. The data is the sum of personal transfers and compensation of employees, as defined in the sixth edition of the IMF’s Balance of Payments Manual (IMF, 2009; Ratha, 2003; World Bank, no date).

Reliability: It is difficult to collect remittance data due to the nature of the data (IMF, 2009) and there is a considerable room for improvement in the collection of such data (Gubert, 2017).

Source: KNOMAD/World Bank (2021): Remittance Inflows / Outward Remittance: Available here (accessed: 14.04.2022)

Local Patterns

The map contains a lot of information, we therefore recommend starting to concentrate on a country of interest.

Let’s take Nepal as an example: Even if the area does not stand out as prominently as other countries in Asia (e.g.

China, India, Philippines), one realizes remittances are crucial for this country when having a closer look at the

share of the incoming remittances as a share of the GDP. It contributes about a fourth to the GDP from 2017 to 2020.

Nepalese are motivated to emigrate the country due to attraction of overseas employment (Gurung, 2020). The

destination are, as we can see on the map, the Gulf States, Malaysia, India and the US. Gurung also mentions Korea

as a destination country, which isn’t represented in our data and again indicates the lack of reliable migration data

(2020).

Global Patterns

To sum up, one can simplify the global pattern of remittances in generalizing in either receiving or sending countries.

However, there are also countries where the amount of sent and received remittances is equalized, as for example

Italy in 2018. In the European region the Balkan States, east-European countries, as well as Portugal and Spain are

receiving countries, whereas Greece, Switzerland, Luxembourg, The Netherlands stand out with a high amount of sent

remittances. Focusing on Switzerland, the largest immigration flows come among others from Portugal, Spain,

northern Macedonia, Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina - all receiving countries. Thus, correlations can be made between

migration data and remittances. Unfortunately, the nature of the migration stock data makes it impossible to

highlight large migration corridors that have emerged recently (i.e. Syria – Turkey).

Exploring our Personal Stories

Dilip Ratha says in his Ted Talk (cf. Background) "my story is not unique", you do not have to go far in your social

environment to get in touch with remittances and migration. Think about your social environment in your country and

the stories of your family and friends. Explore the map: are these stories evident on the map? Such an observation

about the patterns can be drawn in every region of the world.

Further links

Scientific Literature KNOMAD (2019): Migration and Remittances - Recent Developments and Outlook.

Map about Remittance costs Our World in Data (2021): Remittance costs as a proportion of the amount remitted, 2021.

Interactive World Migration Report International Organization for Migration (2022): World Migration Report 2022

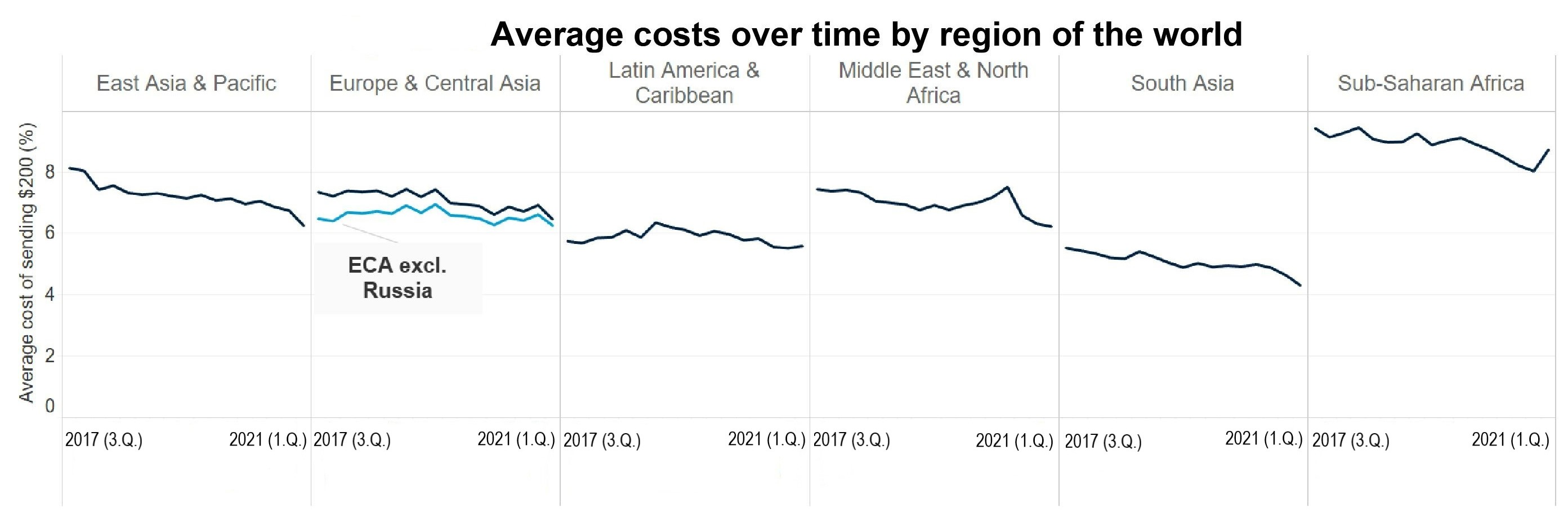

Outlook: Reduction of Transaction Costs

Transaction costs have decreased globally in the past years.

The relevance to reduce transaction costs is shown by Gubert (2017): a discount for

remittance fees lead to a large increase in the number of transactions and the total amount remitted. The SDG 10.c

goal could be indeed expedient, however the question of how to stimulate the use of remittances effectively remains (Gubert, 2017). As an outlook, climate change is likely to result in increased

frequency and severity of disasters, which then ends in an even higher dependency on remittances (KNOMAD, 2016).

As a further step, combined with climate forecasts, remittance dependencies in the future can be identified to go

into action to improve the state now and in the future.

Literature

Dilip Ratha (2003): ‘Workers' Remittances: An Important and Stable Source of External Development Finance’. Global Development Finance 2003, World Bank.

Dilip Ratha (2014): The hidden force in global econimics: sending money home. TED Talk. available at: https://www.ted.com/talks/dilip_ratha_the_hidden_force_in_global_economics_sending_money_home?language=en (accessed: 24.04.2022).

Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD) (2016): Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Outlook. Washington DC.

Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD) (2019): Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Outlook. Washington DC.

Gubert, F. (2017): ‘Migration, Remittances and Development: Insights from the Migration and Development Conference’, Revue d’Economie du Developpement, 25(3–4), pp. 29–44.

Gurung, D. K. (2020): ‘Pattern, Structure and Consequences of International Migration in Nepal’, in Banerjee, A., Jana, N. C., and Mishra, V. K. (eds) Population Dynamics in Contemporary South Asia: Health, Education and Migration. Singapore.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2009a): Balance of payments and international investment position manual. Washington DC.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2009b): International Transactions in Remittances: Guide for Compilers and Users.

International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2017): ‘Follow-up and review of migration in the sustainable development goals’, No. 26 International dialogue on Migration. Geneva.

Migration Data Portal (no date): Migration data and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). available at: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/sdgs?node=0 (accessed: 14.04.2022).

United Nations (UN) (2021): The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021. available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/ (accessed: 25.04.2022).

United Nations (UN) (no date): Putting a spotlight on the role of migrant remittances in achieving the SDGs. available at: https://www.un.org/hi/desa/putting-spotlight-role-migrant-remittances-achieving-sdgs (accessed: 14.04.2022).

World Bank Blogs (no date): Dilip Ratha: Lead economist, Migration and Remittance and Head of KNOMAD. available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/team/dilip-ratha (accessed: 24.05 2022).

Images

Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD) (2019): Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Outlook. Washington DC.

United Nations (UN) (no date): Make the SDGS a reality. available at: https://sdgs.un.org/ (accessed: 31.05.2022).

Master Student GIS

annina.ardueser@uzh.ch

Master Student GIS

silvan.caduff@uzh.ch

Bachelor Student

fionaastrid.federer@uzh.ch