Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

An international research team led by ETH and University of Toulouse, and including scientists from the Department of Geography at UZH has shown that almost all the world's glaciers are becoming thinner and losing mass - and that these changes are picking up pace. The team's analysis is the most comprehensive and accurate of its kind to date.

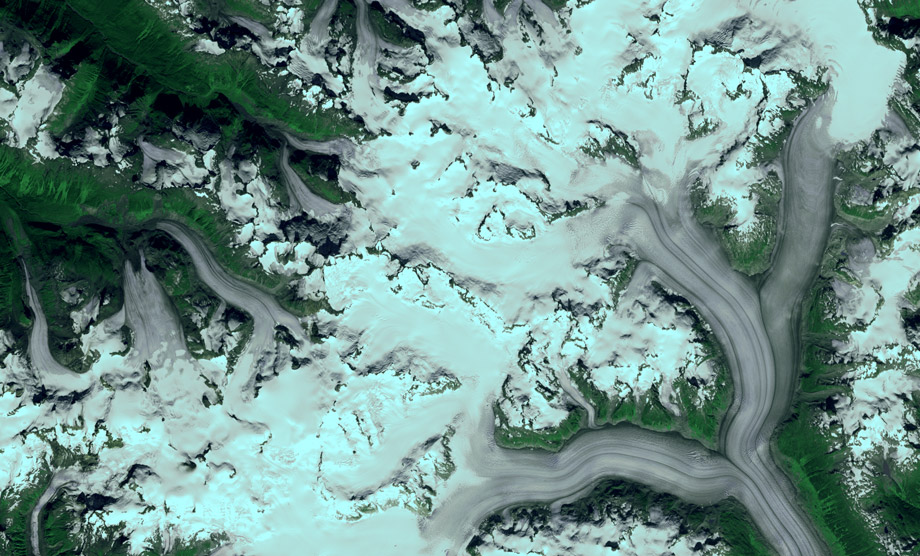

Glaciers are a sensitive indicator of climate change - and one that can be easily observed. Regardless of altitude or latitude, glaciers have been melting at a high rate since the mid-20th century. Until now, however, the full extent of ice loss has only been partially measured and understood. Now an international research team has authored a comprehensive study on global glacier retreat, which was published online in Nature on 28 April. This is the first study to include all the world's glaciers - around 220,000 in total - excluding the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. The study's spatial and temporal resolution is unprecedented - and shows how rapidly glaciers have lost thickness and mass over the past two decades.

What was once permanent ice has declined in volume almost everywhere around the globe. Be-tween 2000 and 2019, the world's glaciers lost a total of 267 gigatonnes (billion tonnes) of ice per year on average - an amount that could have submerged the entire surface area of Switzerland under six metres of water every year. The loss of glacial mass also accelerated sharply during this period. Between 2000 and 2004, glaciers lost 227 gigatonnes of ice per year, but between 2015 and 2019, the lost mass amounted to 298 gigatonnes annually. Glacial melt caused up to 21 per-cent of the observed rise in sea levels during this period - some 0.74 millimetres a year. Nearly half of the rise in sea levels is attributable to the thermal expansion of water as it heats up, with meltwaters from the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets and changes in terrestrial water storage accounting for the remaining third.

Among the fastest melting glaciers are those in Alaska, Iceland and the Alps. The situation is also having a profound effect on mountain glaciers in the Pamir mountains, the Hindu Kush and the Himalayas. Major waterways such as the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Indus rivers are fed by Himalayan glaciers. Right now, this increased melting acts as a buffer for people living in the region, but if Himalayan glacier shrinkage keeps accelerating, populous countries like India and Bangladesh could face water or food shortages in a few decades. ''The situation is similarly worrying for the Tropical and Central Andes, where glaciers are crucial for sustaining river flows on the dry summer months and periods of drought'', explains Inés Dussaillant, co-author of the study and researcher at the Department of Geography. The findings of this study can improve hydrological models and be used to make more accurate predictions on a global and local scale.

To their surprise, the researchers also identified areas where melt rates slowed between 2000 and 2019, such as on Greenland's east coast and in Iceland and Scandinavia. They attribute this divergent pattern to a weather anomaly in the North Atlantic that caused higher precipitation and lower temperatures between 2010 and 2019, thereby slowing ice loss. The researchers also discovered that the phenomenon known as the Karakoram anomaly is disappearing. Prior to 2010, glaciers in the Karakoram mountain range were stable - and in some cases, even growing. How-ever, the researchers' analysis revealed that Karakoram glaciers are now losing mass as well.

As a basis for the study, the research team used ASTER stereoscopic imagery captured on board NASA's Terra satellite, which has been orbiting the Earth once every 100 minutes since 1999 at an altitude of nearly 700 kilometres. This allowed to create high-resolution digital elevation models of all the world's glaciers and to reconstruct a time series of glacial elevation changes since 2000. "With this approach, we could calculate the volume of ice lost by all the world's glaciers over the last 20 years and most importantly, observe the unceasing acceleration of this loss at a global scale throughout the observed period", says Inés Dussaillant. "The message behind our findings is of political significance. It is of uttermost importance to act now to meet the Paris Agreement and fight to achieve a climate change scenario with reduced greenhouse gas emissions"

This is an adapted version of the press release published on April 28, 2021:

Global glacier retreat has accelerated, ETH Zurich

Literature: Hugonnet R, McNabb R, Berthier E, Menounos B, Nuth C, Girod L, Farinotti D, Huss M, Dussaillant I, Brun F, Kääb A. Accelerated global glacier mass loss in the early twenty-first century, Nature, published online on April 28, 2021. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03436-z